Care homes and retirement housing each face challenges, but the demand for these products will only grow as the country's population ages

Retirement housing

Retirement housing has been a feature of the UK housing market for decades. The bulk of existing stock is sheltered housing for social rent, built using grant funding in the 1970s and 1980s. Much of the balance is made up of owner occupied homes, built by specialised housebuilders such as McCarthy & Stone.

A more investible market is beginning to emerge, however. Demographic and affluence trends show there’s huge potential: an ageing population with vast stores of housing wealth is an attractive customer base. New Zealand, the US and France serve as examples of the potential for retirement housing to grow into a large scale and appealing asset class.

The sector so far

There are 730,000 retirement housing units across the UK, according to the Elderly Accommodation Counsel (EAC). More than half these homes, 52%, were built or last renovated over 30 years ago.

There are two models for developing retirement housing for sale. The first, and simplest, is largely indistinguishable from the traditional housebuilder sale model, with a price premium to reflect the added cost of providing communal facilities such as a residents’ lounge, café or gym. Alternatively, a developer might charge an 'event fee' – a charge when the resident sells their property, usually for a proportion of the sale value – to fund these shared amenity spaces.

It’s only in the last few years that we have started to see institutional investment into the sector. Legal & General assembled Inspired Villages from its acquisitions of Renaissance Villages and English Care Villages in 2017, and has recently made headlines by launching its urban retirement brand Guild Living. ReSI REIT has been building its portfolio of retirement housing, purchasing schemes from Aviva and Places for People. And Goldman Sachs-backed Riverstone aims to build a London retirement housing pipeline worth more than £2 billion over the next two years.

We estimate that more than 570,000 households over 75 could afford to rent a retirement home using the rental income from their main home

Savills Research

More recently, some developers have departed from these traditional models. Auriens and Birchgrove will shortly begin letting retirement homes for private rent, each targeting very different price points. While retirement PRS is unusual today, there are excellent reasons for older people to choose this tenure.

In the case of Goldman Sachs-funded, luxury London scheme Auriens, customers will avoid a stamp duty bill equivalent to over a year’s rent by choosing not to buy. In the case of more mid-market Birchgrove, renting enables residents to unlock the equity held in their former homes. The nation’s largest retirement housing developer, McCarthy & Stone, has also started offering homes to rent in its schemes.

There is significant untapped potential in retirement homes for rent. While many older households own their homes, a rent-to-rent model could help them move into retirement housing while retaining ownership of their family home and avoiding stamp duty.

We estimate that more than 570,000 households over 75 could afford to rent a retirement home using the rental income from their main home.

Size matters

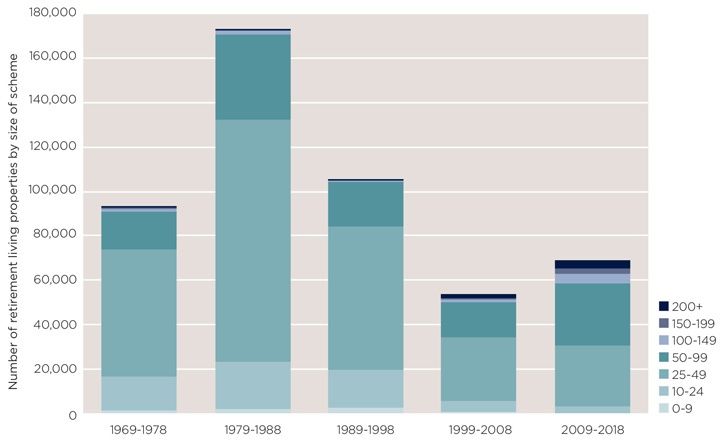

Retirement living schemes by number of units

Source: Savills Research using EAC

Prior to 2000, 80% of retirement housing supply was on smaller schemes with fewer than 50 homes. More recently, the bulk of supply has come from larger developments, with schemes of over 50 homes making up 56% of supply in the ten years to 2018.

As the sector continues to move towards a care-based model, developments will get larger to incorporate efficiencies of scale. Larger schemes can also accommodate a range of tenures more flexibly, as demonstrated by the Extra Care Charitable Trust on their large, multi-tenure developments.

The largest retirement village in the UK today is Lark Hill Village in the West Midlands, with 340 homes. In the future, this size of scheme could become the norm.

Risk and mitigation

Retirement housing currently sits across two planning use classes. The C3 use class is the same as for regular residential developments, and requires a developer to provide affordable housing. The C2 use class requires some kind of care to be provided on site, but without an affordable housing contribution.

Guidance on the amount and type of care needed to qualify as C2 is inconsistent across the country, leading to uncertainty over whether a potential retirement living scheme will be viable. In London, guidance is clearer, in that C2 developments are expected to provide both care and affordable housing, putting them at a disadvantage to C3 schemes.

Clarity on what level of care is required on C2 developments, perhaps through an update to National Planning Practice Guidance, would reduce this uncertainty and could unlock more retirement housing development, particularly if it levelled the playing field for schemes in London.

Some retirement living providers have ‘event fees’, charging former residents a proportion of the property’s value on resale. Poor communication of what these fees pay for and when they are levied has harmed the sector’s reputation.

Government has promised to implement the Law Commission’s recommendations for event fee reform, including restrictions on when they can be charged and standardised information to be included in marketing and sales documents. New Zealand, which has a better-established retirement living sector, enacted similar legislation back in 2003.

This suggests that greater transparency around event fees could help rebuild trust between residents and developers, enabling faster retirement housing delivery.

Evolution

We estimate that the 730,000 retirement housing units across the UK are worth just under £100 billion. Accounting just for today’s over-75 population, we believe that the retirement living sector could grow to 1.7 million homes at full maturity. This is an increase of 138% over current stock. Accounting for population growth, this figure would be even higher.

We noted in our earlier publication (Spotlight on Retirement Living, 2018) that the supply of sheltered homes for social rent is in line with need. This additional stock will, therefore, comprise a mix of market sale and intermediate homes, either privately rented, shared ownership, or new products such as rent-to-rent. The mix of different housing tenures and types required affects the values of these homes.

.jpg)

Accounting for the tenure of this additional stock, we estimate that at full maturity the UK’s retirement housing sector could be worth £244 billion.

To put this figure into context, we have calculated the value of housing owned and occupied by the over 65s to be over £1.6 trillion. Much of the increase in the value of the retirement housing sector could be funded through older people choosing to downsize. The challenge here will be providing a product that can tempt these older residents out of a home they’ve likely lived in for decades.

The potential benefits of a larger retirement living sector are substantial. Offering homes that allow older people to age in place, retirement villages can help free up much needed family housing, reduce the nation’s social care costs, and address feelings of isolation and loneliness in the older population. Based on research from Demos and The Aston Research Centre for Healthy Ageing, government saves between £1,000 and £1,540 per year for each person moving into retirement housing with care.

Care homes

Almost 420,000 people live in elderly care homes in the UK, accounting for just under 15% of the population aged over 85, according to LaingBuisson figures. The ONS projects a 36% increase in the 85+ population by 2025, and we expect to see a corresponding increase in care home demand.

However, despite the demographic drivers supporting care home demand, some operators are facing financial pressure due to a heavy reliance on local authority-funded residents.

Investment

Elderly care home investment was £1.3 billion in 2018 across 26 deals. That’s almost double the investment we saw in 2017, £0.7 billion, despite a similar number of deals (24). Net initial yields averaged 6.6% in 2018, slightly down from 6.9% the previous year. While average yields only compressed by 22 basis points, last year also saw three transactions with yields below 4.0%, with Aberdeen Standard paying a record low 3.75% for Moore Place in Esher.

Just two deals made up more than half the value invested last year: Aedifica’s acquisition of the Forest portfolio from Lone Star, and Chinese private equity firm Cindat’s purchase of HCP’s Ice portfolio. This interest from overseas marks a change from 2017, when 74% of investment volume in elderly care homes was domestic.

The long lease lengths and indexed rents on care home leases make them attractive for investors. Leasing to an operator means investors can expect a stable, steady rental income stream, similar to more established property sectors such as offices.

Risk and mitigation

Four Seasons has dominated recent elderly care headlines with their fall into administration. This comes alongside a 33% increase in insolvencies for elderly and disabled care homes between 2017–18 and 2018–19, according to our analysis of Insolvency Service figures.

Care homes are funded through a mix of sources. Residents with more than £23,250 in savings (more in Wales and Scotland) must pay for care themselves, while local authorities fund care for those below this savings threshold.

Local authority funding for care homes is severely restricted, with the state paying substantially lower rates than an individual funding their own care. This puts financial pressure on care homes with a high proportion of local authority-funded residents. Without reform, we are likely to see more care homes close as they struggle to remain profitable on local authority fees.

In spite of these funding challenges, the UK’s ageing population will drive growing need for elderly care. For the many care home operators attracting a high proportion of private paying residents, it’s possible to deliver strong and sustainable returns.

Evolution

We estimate that, in pure numbers terms, the amount of care home places available today is broadly in line with need.

That’s not to say there is no potential for growth, however. As with retirement housing, many of the UK’s 470,000 care beds are in dated buildings with facilities that are no longer fit for purpose. The number of care beds is decreasing year on year, as unviable, smaller or older homes close faster than the restricted rate of new development. As stock levels fall and the number of older people increases, we expect a swell of demand for new care home development over the next few years.

While there are many reasons a person might move into a care home, one of the most common causes is the onset of dementia. The Alzheimer’s Society reports that 70% of elderly care home residents in 2019 had dementia or severe memory problems, and one in six people aged over 80 across the UK suffered from the illness. PHE estimated that 645,000 people aged over 65 in England had dementia, of whom just two thirds (68%) had a diagnosis.

These conditions require careful management. While retirement housing may be suitable for helping older people live independently without care for longer, even the best-designed retirement village cannot hope to care for dementia patients without specific care facilities and staff on site.

As the population with conditions such as dementia grows, the need for care homes and dementia care facilities will rise in turn. We would expect demand for retirement housing to be strongest on village schemes offering the option of residential and dementia care on site, so that residents are able to age in place.

Read the articles within The Sky's The Limit? below.

.jpg)

.jpg)