UK Prime overview

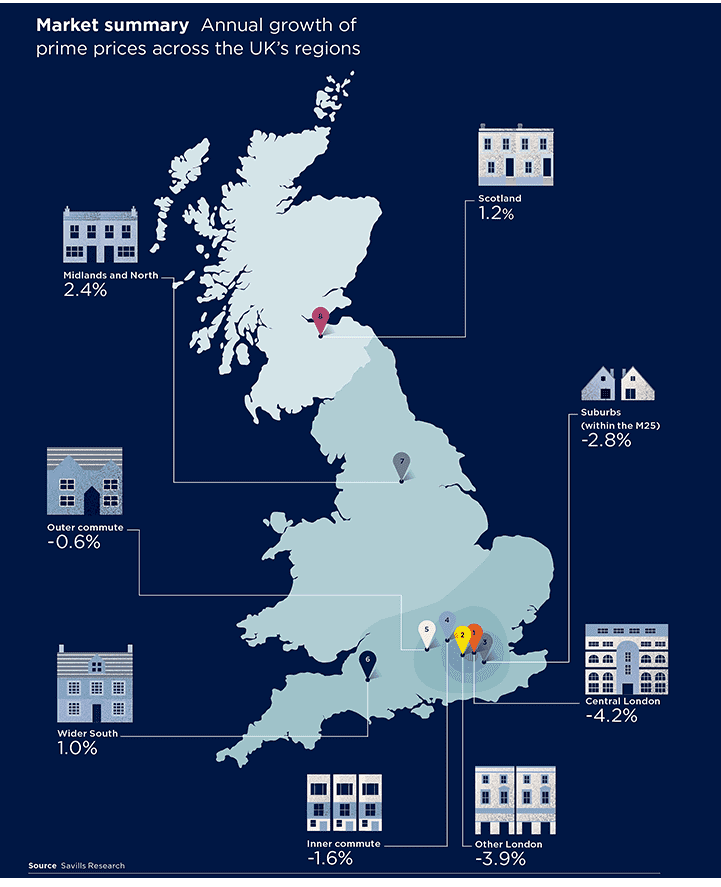

While the markets for prime properties in Scotland and the North continue to grow, London remains sluggish, with evidence of a reverse ripple effect in the capital’s commuter zone

While the markets for prime properties in Scotland and the North continue to grow, London remains sluggish, with evidence of a reverse ripple effect in the capital’s commuter zone

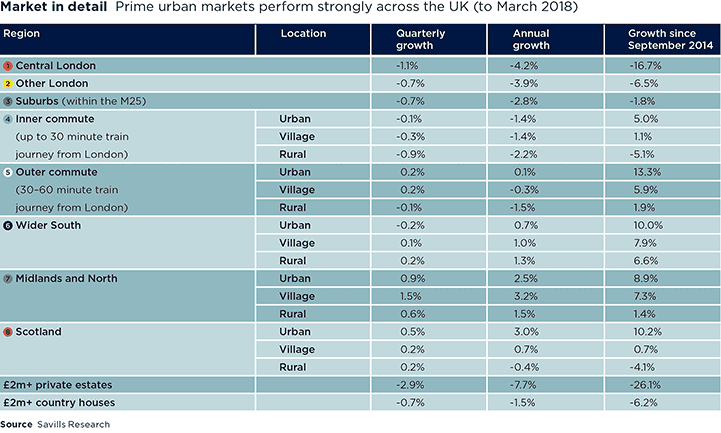

Values in the prime central London market are now 17% below their 2014 peak. This downturn has been different to previous ones, being more drawn out and less acute than, say, the early 1990s and post credit crunch. While it was sparked by the stamp duty changes of December 2014, values have been gradually eroded by wider changes in the tax regime and political uncertainty.

Historically, we have seen the central London market bounce back quickly, as overseas buyers took advantage of weaker sterling. However, the additional factors surrounding tax and uncertainty have made those buyers more cautious. Equally, there haven’t been the unique safe haven drivers there were in, say, 2009, given the recovery in the global economy.

▲ Riverwalk, London

Elsewhere in London, price adjustments of prime property have been less pronounced. But without impetus from the centre, prices are, on average, 6.5% below where they were in September 2014, having declined 3.9% over the past 12 months.

This sits in context with a pretty sluggish mainstream market in the capital, which has gone from double-digit growth to little, if any.

However rich in equity, the cost and availability of debt is an important driver in domestic prime markets – typified by the belt running from Fulham to Wimbledon in South West London. So, much like the wider London mainstream market, these areas seem to have hit the limits of mortgage regulation. This has come at a time when the expectations for interest-rate rises are being brought forward rather than pushed back.

Beyond London, the market is not as stretched. With lower levels of price growth in the run up to 2014, it’s been less exposed to these factors.

However, with less housing equity being exported out of the capital, there is evidence of a reverse ripple effect emanating from the subdued prime London market.

Though able to sustain modest house price growth in the immediate aftermath of the stamp duty changes of 2014, prime suburban markets within the M25, such as Cobham, Esher, Weybridge, Loughton, Northwood and Rickmansworth saw annual house price growth slip into negative territory in the autumn of 2016.

On average, prices have only fallen 1.8% in total since then. However, the top end of this market, where buyer profiles are most closely aligned to central London, has had much more of a reality check.

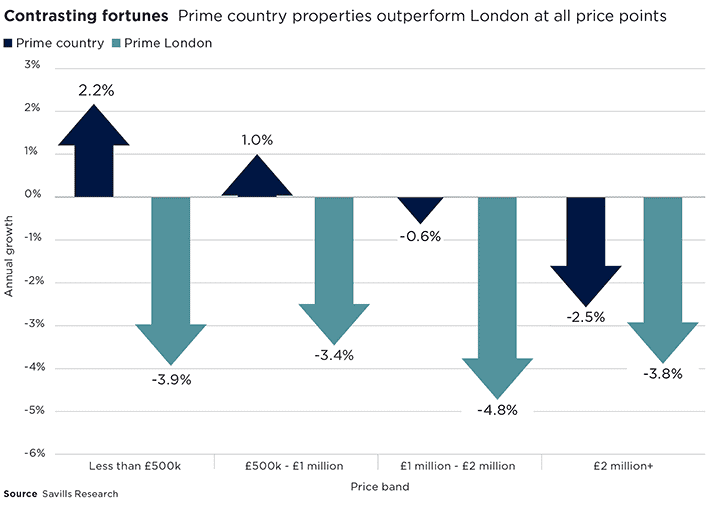

In the market above £2 million (typified by properties on the private estates of the home counties), prices peaked at the same time as in London and are now 16% lower than they were five years ago.

By contrast, prices in the £1 million to £2 million market have risen 16% over the same period. Between £500,000 and £1 million, they are up 26% over five years.

Further evidence of this reverse ripple came as growth slowly evaporated in the spring of 2017 in the parts of the commuter zone closest to London. In the autumn, that spread to the outer commuter zone, typically within one hour of London.

Across these two commuter zones, prime properties in the most desirable towns and cities have significantly outperformed their counterparts in village and rural locations over the past five years, as townhouses have risen in popularity relative to the traditional farmhouse, rectory or manor house.

However, muted annual price movements no longer show any significant variation across these locations. That means, for the moment at least, the average premium for space in a prime urban location has topped out at around 30% in the commuter zone.

More widely across the South of England and South Wales, price growth remains in low, single-digit territory, much as it has done for the past three years.

Across this broad swathe of the country, the peak of the prime rural housing market was in 2007, though the extent to which that applies varies.

In the long-established prime markets of the Cotswolds, where demand is spread across full-time residents, part-time commuters, weekenders and second home owners, values are within 1% of that benchmark. By contrast, in more discretionary coastal markets of Cornwall, Devon, Suffolk and Norfolk, they sit 10% below their pre-credit crunch high.

The prime urban markets in cities such as Bath, Bristol and Cheltenham surpassed their previous peak in 2015 and, since then, have seen price growth of a further 6.5%, albeit that annual price growth remains a modest 0.7%.

▲ Broadway, Worcestershire

The prime property market in the Midlands and the North of England has been price sensitive for most of the past decade, though it has sustained modest growth for the last four years as we have shifted to a new stage in the housing market cycle.

Much like the rest of the country, demand has been strongest for townhouses in places such as York, Chester and Nottingham.

The best urban properties in the best addresses have risen by 17% during the past five years, while the wealth generated out of Manchester has driven price growth in the affluent suburbs and villages such as Wilmslow, West Didsbury and Alderley Edge.

By contrast, manor houses in village and rural locations across the wider region have struggled to show any consistent value growth during this period and are only just beginning to benefit from the wider pick-up in the region.

▲ Precentors Court, York

During the past five years, the prime housing market north of the border has faced its own headwinds, albeit from familiar sources. Political uncertainty came in the form of the independence referendum some time before Brexit took centre stage.

Greater exposure to taxation manifested itself in the punitive Land and Buildings Transaction Tax, which replaced stamp duty in April 2015.

Despite that, the prime market in Scotland in 2017 was the best for a decade – though the difference between town and country markets is more marked than anywhere else across Great Britain.

Prices in the rural markets are, on average, still 29% below their 2007 peak, having slipped marginally in the past year. So, on average, £1 million would buy you 5,500 sq ft of living space in the Scottish countryside – three times the space that £1 million would buy in the suburban market of Esher in Surrey.

By contrast, the prime markets of Edinburgh and Glasgow are respectively within 3% and 10% of that highwater mark. Prices of townhouses in Scotland’s capital city have increased by just over a quarter in the past five years, with annual price growth still coming out at 4.5%.

▲ Glebe House, Kirkoswald, Maybole, Scotland

4 other article(s) in this publication