Land value

Delivering the Letwin Review’s proposals may reduce GDV and limit land value uplift. How can the government and stakeholders balance competing priorities?

.png)

Delivering the Letwin Review’s proposals may reduce GDV and limit land value uplift. How can the government and stakeholders balance competing priorities?

Increasing housing supply will not only be achieved by diversifying the types of homes available for open market sale. The greatest untapped potential is in delivering alternative tenures. Indeed, the Letwin Review notes the demand for affordable housing is “virtually limitless”.

It is tempting to see the provision of this type of housing as the easiest way to increase build-out rates. However, doing so within current development models poses challenges.

Housing developments with more affordable housing and build to rent will generate a lower gross development value (GDV), although this will be offset by the earlier cash receipt, as build-out is accelerated.

The Review acknowledges that it is not realistic to require housebuilders to lower the selling price of their current product, but this wider tenure mix will restrict GDV and the uplift from existing-use value.

The current rate of affordable housing delivery on most sites is limited by the need for subsidy from open market sales on the rest of the site. Government funding for affordable housing is £9 billion for 2016-2021, with a further £2 billion recently announced to be available after 2021. This is the first time government has pledged funding beyond the current spending review period, and will provide more certainty to support the delivery of affordable housing. However, there is not enough money to fund the volume of affordable housing that is required.

So, expanding delivery will have to be done either through increased developer contributions, or the housing association cross subsidy model, both of which eat into the available land value uplift. There is, therefore, a need to balance the tension between increasing current rates of land value capture and ensuring that the returns from developing homes are enough to incentivise landowners and developers.

Crucially, to maintain the expansion of housebuilding, developers also need to be able to maintain margins which are high enough to cushion the business in the event of a market downturn.

Potential for land value capture

The potential to capture land value uplift varies significantly across the country, in line with the sales values of the new homes.

In 2012, we calculated that delivering 30% affordable housing alongside at least £3,000 per plot in Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) and Section 106 was viable in only 38% of English local authorities outside London, although the proportion has increased significantly since then.

We estimated that around 50% of land value uplift is captured via developer contributions, accounting for site remediation and enabling

Savills Research

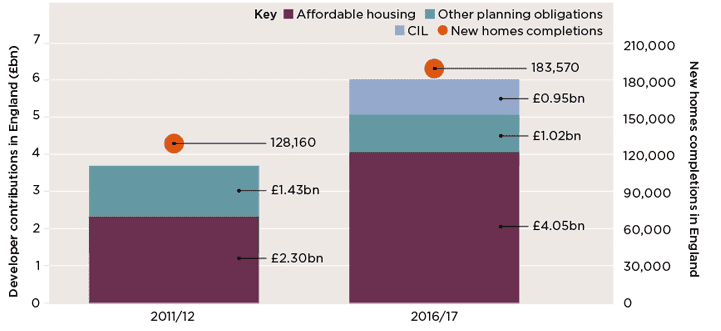

According to MHCLG research, developer contributions in 2016/17 amounted to £6 billion. This was made up of £4 billion in affordable housing, £1 billion in CIL, and a further £1 billion in Section 106 agreements.

.png)

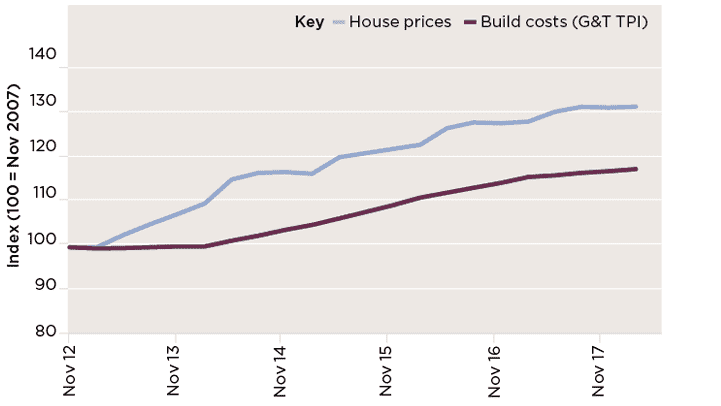

This is a 60% increase from 2011/12, partly supported by national average house price growth of 30%, while build costs have only increased by 16% since 2012. Consequently, affordable housing, CIL and Section 106 can be delivered by more sites in more markets in 2018 compared with 2012, while still providing a reasonable return to the landowner and profit for the developer.

Land value capture Since 2011/12 there has been a 43% increase in completions, but a 60% increase in developer contributions

Source: MHCLG

We have estimated that around 50% of land value uplift is captured via developer contributions, once the costs of site remediation and enabling are factored in. By this measure, developer contributions are working.

Crucially, the rest of the value uplift is usually not all received by the landowner. Much of it funds the complex and lengthy business of masterplanning and enabling sites, with all of the market and planning risk that entails.

The trend of an expanding pool of land value uplift is unlikely to continue over the next five years. We are forecasting much lower house price growth of only 14% during the next five years, meaning the amount of uplift available for land value capture will not expand as rapidly as it has since 2012.

House price growth Affordable housing and CIL/S106 can be delivered by more sites in more markets in 2018

Source: Nationwide, Gardiner and Theobald

Balancing priorities

To deliver the ambitions outlined in the Letwin Review and ultimately work towards solving the housing crisis, there has to be a way to capture the optimum share of a limited pool of land value uplift. But there is a limit to how much further land value capture can be pushed before landowners are unwilling to bring their sites forward for development. A willing landowner will require a reasonable receipt that compensates for loss of the land and any income it generates.

The question is, what can the government do to balance these competing priorities and ensure that developers deliver more diversified schemes?

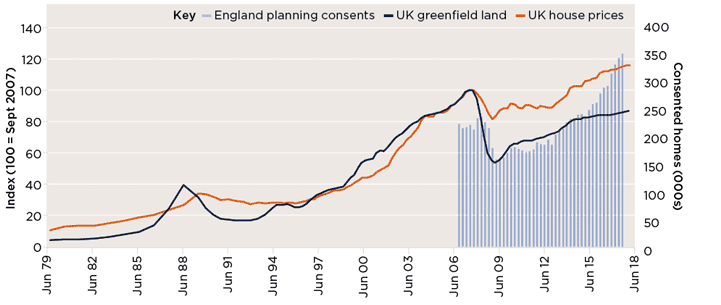

Land value growth Increased supply of consented sites has helped moderate land values

Source: Savills Research, Nationwide, HBF

Government action

The most important thing is to increase land supply, particularly in the highest demand areas.

At a national level, higher land supply has already been seen to moderate development land value growth which allows developer contributions to be made viably. Between 2007 and 2017, the number of residential consents granted increased by 58% from 222,000 to 350,000 plots, with the growth following the introduction of the NPPF in 2012 (see above).

Over the same period, UK greenfield development land value growth has been muted, remaining 13% below its former peak level in 2007. In contrast, UK house prices are now 15% above their 2007 peak.

The exceptions are the most land-constrained and highest demand markets: predominantly those in and around London. Planning restrictions, including Green Belt, have limited the supply of development land, alongside a rapidly declining stock of previously developed land.

This has led to high levels of competition for sites, and competitive bidding has resulted in higher land prices. Our greenfield land index is 13% below its former peak nationally, but in the South East values are only 3% below 2007 levels. Without substantive change to Green Belt policy, a significant increase in land supply in these areas is unlikely. This is where an alternative approach is required.

Higher land supply has been seen to moderate development land value growth

Savills Research

Policy clarity

In areas where land supply is limited, the key to delivering the ambitions of the Letwin Review is to give clear and explicit requirements for development contributions, particularly in very competitive land markets.

This means having an up-to-date local plan in place, which sets a realistically ambitious but achievable requirement for affordable housing provision alongside other developer contributions.

If the local plan policies are clear to all parties from the start, land will be priced by developers on that basis. This prevents landowners from forming unrealistic expectations of land values, removing barriers to delivery.

However, local authorities need to set requirements that are ambitious but will still produce reasonable returns for landowner and developer. In urban locations, this becomes more complex. Sites may already have an existing-use value that is higher than the residual land value for housebuilding, or a sale for an alternative use such as distribution would give the landowner a better return.

If government is too aggressive in using affordable housing without providing any additional grant funding to boost build-out rates and seeking other developer contributions, the unintended consequence may be to remove the incentive for land to come forward for housing at all.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING

We estimate sub-market housing need at 100,000 homes per year in England. Since 2013, delivery rates have averaged 45,000 homes per year, with the majority of the shortfall in London and the South East. It would take at least £7 billion of grant funding each year to provide social rented homes to all of those in need of sub-market housing. Current funding is £9 billion for the 2016-2021 period. We await the final policy recommendations of the Letwin Review to see if there are any proposals to fill this funding gap. There have already been positive signals with the recent announcement of a further £2 billion of funding after 2021.

.png)

IS COMPULSORY PURCHASE THE ANSWER?

It has been suggested that using a lower basis of compensation payable under compulsory purchase powers, or the threat of it, would be enough for landowners to accept significantly lower land values. However, the scale of housing development required to meet need (300,000 homes each year in England, 14,000 in Wales and 25,000 in Scotland) means that using compulsory purchase would be expensive, time-consuming and it is doubtful that local authorities and Homes England would have enough resource to do so.

2 other article(s) in this publication