Text: Matthias Pink

Once upon a time, residential property was an integral component of the portfolio mix for German institutional investors. In the 1970s, for example, asset allocations to residential property by life insurance companies and pension funds were constantly above 5%. In the decades that followed, apartments represented an increasingly smaller proportion of the portfolios of both these and other investor groups. By the dawn of the financial crisis, residential property accounted for just 0.3% of the portfolios of direct insurers in Germany. Even the portfolios of the German open-ended real estate funds included scarcely any residential property anymore. What had happened? In view of the low initial yields and greater protection for tenants, institutional investors increasingly avoided residential property from the 1980s onwards. Instead, they devoted their attention to commercial property.

Today, initial yields are lower than ever and the state is increasingly intervening in the apartment market. However, apartments continue to enjoy levels of demand from institutional investors that have not been seen for a long time. The strong risk aversion among institutions following the shock of the financial crisis smoothed the path for residential property to make a comeback into investment portfolios. To this day, limiting risk remains the utmost priority and stable returns are sought first and foremost. The German rental apartment market is tailor-made for this requirement profile. In fact, it always has been. However, the majority of investors simply preferred other investments in previous decades. The high levels of letting activity in recent years have certainly contributed to the rediscovery of the apartment market by investors.

The comeback is also perhaps best illustrated with reference to German insurance companies and pension funds. Over the last ten years, these have been responsible for net investment of €1.9bn in the German apartment market. Their directly-held apartment stock, which totalled €3.4bn at the end of 2008, has grown accordingly (although concrete figures are no longer available owing to changes in reporting obligations). Together with their foreign counterparts, these have invested a good €3bn, representing the fourth largest purchaser group of the post-Lehman era.

However, apartments have not only found their way back into the portfolios of insurance companies, pension schemes and pension funds by way of direct investment. These and other institutional investors have also increased their exposure to apartments indirectly. One way they have done so is via special funds, which have accounted for net investment of a good €13bn in the German apartment market over the last ten years and whose main source of capital is insurance companies, etc. Another way, which has only occurred in Germany over the last few years, is via the stock exchange. Prior to the financial crisis, listed residential property companies scarcely came into the equation. Today, they include five of the ten largest apartment owners in Germany. These five companies combined hold more than 800,000 apartments and have a total market capitalisation of around €50bn. Among their largest shareholders are insurance companies, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, for example, holds shares in the three largest companies. Mathematically speaking, therefore, the fund “owns” more than 40,000 German apartments.

In brief, this can all be summarised as follows: institutional investors have rekindled their passion for residential property. The risk aversion of investors, which peaked during the financial crisis, has brought the two back together. Will the romance be short lived? The characteristics of residential property alone, namely stable income and hence modest prospects of short-term capital growth, favour a longer-term relationship. Moreover, such stable returns that are independent of economic conditions are particularly valued by investors in this late stage of the cycle (see the following page). Evidently, however, investors’ preferences are no match for the income from apartments when it comes to stability. From time to time, their eyes will wander.

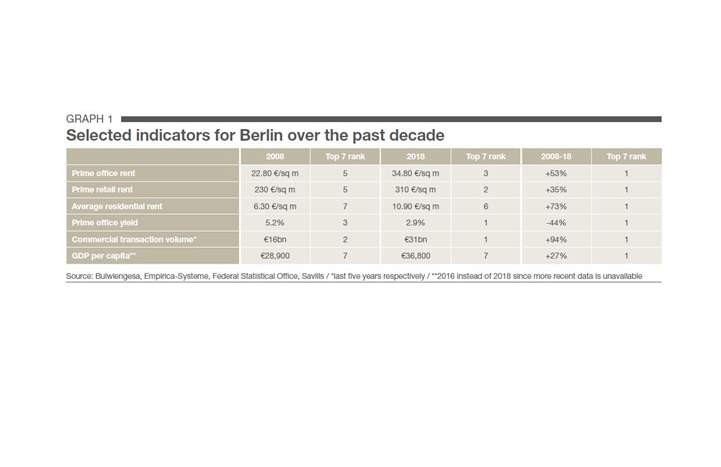

Over the last ten years, the scepticism of real estate investors towards Berlin has given way to a euphoria that is manifested in their willingness to pay. Prime office yields, for instance, are on a par with those in Frankfurt and Munich. Since the capital continues to lag behind the other top seven cities significantly in terms of economic output, the low yields surely reflect high expectations of future growth in Berlin, among other factors. In fact, Berlin has closed the gap in economic performance over the last ten years and the ongoing vibrant start-up scene, combined with the sustained influx of creative minds into the city, promises further growth. One notable product of this phenomenon is Zalando. Formed in the same year that Lehman Brothers filed for insolvency, the online retailer is now among the fifteen largest companies in Berlin and has accounted for one of the largest requirements in the office lettings market in recent years. Today, Berlin still produces more than 500 start-ups per year. Most will certainly fail but many will establish themselves and some may even become the next Zalando. With such a vast number of new businesses, randomness alone dictates that it will also produce success stories. In addition, more and more established companies are moving into the capital to be close to Berlin's technology and start-up scene. In this regard, the prospects that Berlin’s catching-up process will continue over the coming decade are good. Real estate investors are certainly betting on this. However, they should also be mindful of the fact that the new economy emerging in Berlin is more vulnerable to economic fluctuations than its public-sector-led predecessor. Hence, short-term setbacks on the long-term growth trajectory should also be expected in the real estate market.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)