With prices directly affected by political, economic and technical pressures, 2019 could prove to be a volatile market

The energy market is a complex web of connections and correlations, in which localised events quickly ripple out to affect the entire sector. Not surprisingly then, it can be volatile, with prices buoyed or buffeted by political, economic and technical pressures. Last year saw plenty of these, and the result was a year of fluctuating prices: from January to December 2018, prices ranged from just over £42/MWh to nearly £66/MWh for electricity, and from 42p/th to 68p/th for gas, with plenty of rises and falls along the way. In 2017, the ranges were approximately £40–£46/MWh and 41p–48p/th.

Last year we saw a perfect storm of events. Renewable energy generation was lower than expected; the global demand for gas and coal rose; the uncertainty over Brexit affected the strength of the pound

Savills Energy

“Last year we saw a perfect storm of events,” says Shaun Greenwood of Savills Energy. “Renewable energy generation was lower than expected; the global demand for gas and coal rose; the uncertainty over Brexit affected the strength of the pound; and maintenance issues and lack of storage throughout Europe created practical problems.”

Following a steady upward trajectory from January to September, prices for both electricity and gas fell sharply in the last three months of 2018, although towards the end of December prices in Europe surged due to a lack of wind, unplanned outages and, in France, the “gilets jaunes” protests, which have included strike action that has closed nuclear reactors. Over the last year as a whole, however, the pricing picture was more varied.

With wind generation reaching 10-12 Gigawatts during peak load hours, reliance on non-renewable sources was eased and electricity prices softened as a result. A surplus of liquefied natural gas (LNG), running counter to pricing signals and forecasts of warmer weather, triggered selling in an already over-supplied market. And as those weather forecasts were proved accurate, wholesale gas prices dropped sharply, setting values into the winter of 2020. In December, LNG imports into Europe reached a record high for a quarterly period thanks to weak demand in Asia and favourable shipping rates, and were helped by below-forecasted production from the Norwegian Continental Shelf as the result of unplanned outages.

This is certainly going to be an interesting year. With all eyes on the UK at the moment, it’s hard not to talk about Brexit and whether a deal will be agreed in time

Savills Energy

The oil market has been highly volatile since June 2018. Oil prices collapsed as the market corrected itself following some artificial upward drivers: market excitement, OPEC’s unfulfilled announcement of production cuts and expectations of a shortage in supply as a result of the USA’s sanctions on Iran. In the event, OPEC was able to make up for the decline in output from Iran, and North American production has reached record-breaking levels. But with too much oil in the market – despite many big producers cutting output – prices have inevitably softened.

As ever, political interventions are contributing too, and not just because of Brexit and sanctions against Iran: the implications of the Government’s energy price cap are beginning to take effect. The cap on the Standard Variable Tariff (SVT), which came into force on 1 January this year, aims to save 11 million domestic customers in the UK about £76 per annum on energy bills. But it is currently being challenged by Centrica, owner of British Gas, on the grounds that it has been set too low by Ofgem, the industry regulator. Centrica estimates that the cap will cost it around £70m over the first quarter of 2019. With the cap estimated to strip £1bn of earnings a year from the energy retail sector, the impact on the industry is likely to be significant (see Supplier Exit below).

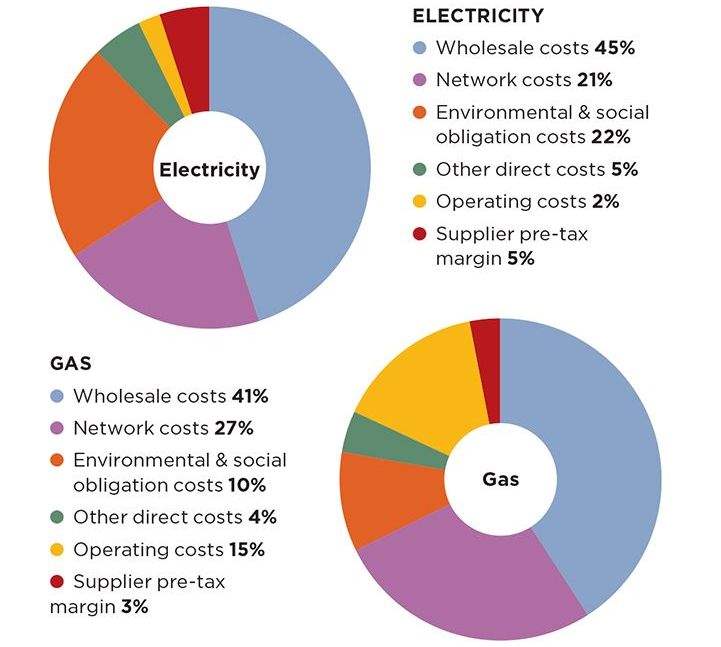

The price cap is pegged to wholesale prices and will be revised twice a year. However, wholesale costs constitute less than half the retail price of energy: 45% for electricity, 41% for gas. The rest of the bill is made up of so-called Third Party Costs that include environmental and social obligation costs, operating and network costs, and supplier margins. The price cap could distort this equation.

Third party costs Non-commodity costs include a number of mandatory charges that make up over 50% of the total bill

Source: Savills Research

“This is certainly going to be an interesting year,” says Shaun. “With all eyes on the UK at the moment, it’s hard not to talk about Brexit and whether a deal will be agreed in time. However, with other events such as the collapse of the SSE/Npower retail merger and its ownership being transferred to E.ON, leading to the loss of 900 Npower jobs, the cancellation of several UK nuclear projects and the confidence of the industry being tested as smaller energy providers close up shop, 2019 won’t be a stable year and we should prepare for a very volatile market.”

.jpg)

SUPPLIER EXIT

With Ofgem tightening its grip on trading and the implementation of new price caps from January, energy suppliers are under ever more pressure, and some have not been able to withstand it. Even SSE and Centrica have posted profit warnings as they struggled with rising wholesale prices and increased competition in the second half of 2018, so it is not surprising that several smaller suppliers exited the market over the past year. In January 2019, Economy Energy and Our Power took the number to 13.

The business model of smaller suppliers is based on undercutting the wholesale prices paid by the Big Six (British Gas, EDF Energy, E.ON, Npower, Scottish Power and SSE), while having lower operational costs and less tax to pay. However, the price cap now places the same limits on all suppliers for the bulk of their customers. Added to this weakening competitiveness is the smaller firms’ lack of equity, which restricts their ability to meet changing obligations relating to green energy and prevents them buying much energy in advance, thus making them vulnerable to increases in the wholesale price. Continuing price rises could see more small suppliers cease trading in the months ahead.

SMART METER ROLL-OUT

In 2009 the Government introduced an £11bn scheme that would see smart meters installed in every home in the UK by the end of 2020. This initiative is part of the Government’s strategy to achieve low-carbon, efficient and reliable gas and electricity resources. The hope is that, with smart meters recording energy consumption (and cost) in almost real time, householders will be able to monitor their gas and electricity use and modify it accordingly; the average household bill is expected to fall by £11 in 2020 and £47 in 2030.

However, the scheme is facing difficulties, as Chris Phillips of Savills Energy points out. “There are concerns that the Government has neither drawn on the full expertise of the energy industry in implementing its scheme, nor looked at the scheme’s limitations, which include the manufacture of the meters, the wireless technology required and the adoption of different meter models,” he says. “In the face of rising costs, and uncertainty about who should pay them, the projected savings appear increasingly ambitious, and the 2020 deadline looks likely to be missed.”

.jpg)

.jpg)