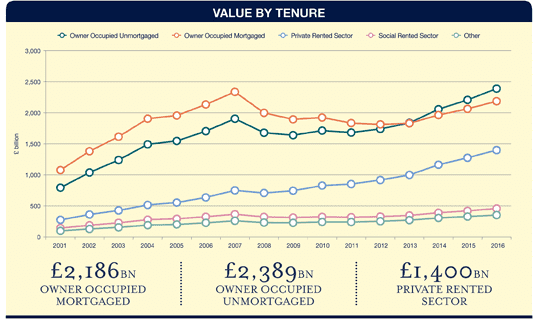

Q The total value of the UK’s housing stock is now £6.79 trillion, 3.65 times the size of its economy. It has risen by £1.5 trillion in the past three years. Can this continue?

A These pretty mind blowing numbers primarily reflect house price growth that has been driven by a combination of low interest rates and, for the most part, a strengthening economy. They mean private housing wealth stands at over £5 trillion for the first time.

But the £1.5 trillion increase has been heavily influenced by the powerhouses of London and the South East, which together have accounted for over one third of the growth.

As we look forward, there is a series of factors that are likely to mean that price growth slows.

As the implications of the decision to leave the EU become clearer, economic uncertainty is likely to feed into weaker consumer sentiment and tighter household finances. We expect price growth to slow across the country for the next two years or so.

After this period of buyer caution, we do expect things to pick up. But rising interest rates will put a squeeze on affordability for mortgaged buyers, especially in the areas of the country that have seen some of the biggest house price increases.

We are already beginning to see this play out. Despite strong annual growth, we have seen three-month on three-month house price growth fall back to 1.7% in December 2016 across the UK as a whole. To put that in context, 12 months previously it was 2.4%.

In London, the change has been more pronounced. The three-month on three-month measure has fallen from 3.7% to just 1.2% over the same period.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)