The annual Savills Impacts research programme, released on 19th May, shows that the Czech Republic holds one of the lowest proportions of land and property in its pension fund investments. Given today’s low interest rate environment amid a rising Czech retiree population and widening deficit between retiree needs and pension provision, this needs to change.

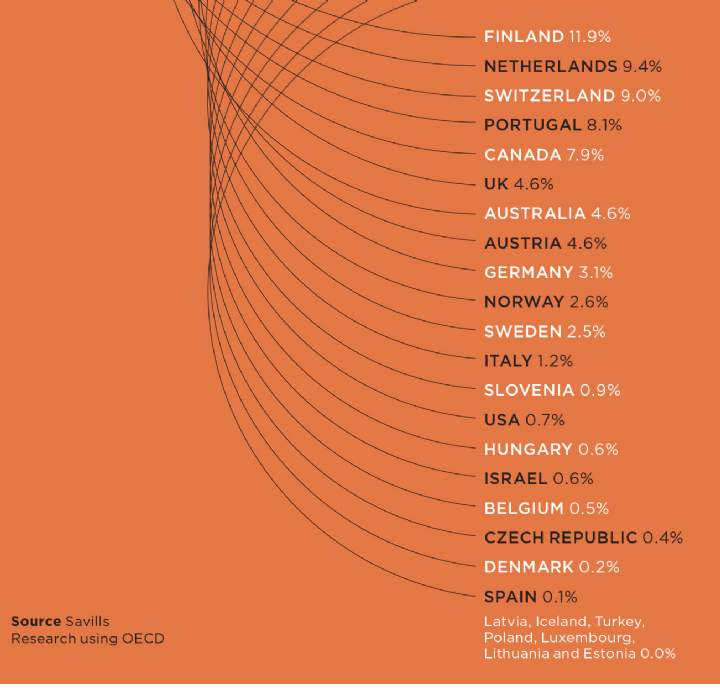

Savills research found that less than 3% of global pension fund assets are held in land and property – a relatively modest allocation, but nonetheless a significant sum of $44 trillion at the end of 2018. The levels vary widely between countries, with Finland at the top with 11.9% of pension assets invested in real estate and the Czech Republic close to the bottom with just 0.4%.

According to the OECD, the Czech Republic had $20.9 billion invested in pension funds at the end of 2018, with the vast majority of that (almost 80%) in low-risk, low-return government bills and bonds, followed by cash and deposits. A miniscule amount was allocated to equities, which contrasts sharply with countries like Poland, which has about 80% of its pension assets invested in that medium. Being invested so conservatively means Czech pension fund returns have been measly, especially given the long-term low interest rate environment. The OECD reports the real investment rate of return of Czech pension funds from December 2017 to December 2018 was in fact -1.6%.

This situation is not sustainable. According to Savills, the deficit between retirees’ needs and pension provision is growing by $28bn every 24 hours. By 2050, the deficit is set to be five times the size of the global economy and the threat of this enormous financial burden is signalling a ‘tipping point’ that is fuelling demand for long-term secure income streams, with real estate seen as a good annuity match.

Too conservative by half

Why are Czech pension funds so resistant to investing in real estate? Experts believe it’s mainly a function of these funds being run very conservatively, which is itself partly down to regulation. Czech pension funds are required to post positive nominal returns in every calendar year regardless of either market conditions or the trend in returns over the long run. Regulations also do not require pension funds to offer a selection of different investment strategies to their investors, so pension funds are not motivated to offer anything other than the current tried-and-tested strategy of investing in bonds, which provides stable, slightly positive nominal returns. Shifting towards riskier assets from bonds just doesn’t make much sense to risk-averse pension fund managers.

However, rising needs for greater pension provision will mean that more Czech pension and annuity fund money will have to target the real estate sector, as it recently has seen to be doing. The challenge for these pension funds over the next decade is that they will be competing for such long-income assets with other institutional capital – and not just domestic capital – at a time when the availability of high-quality stock remains low and prices are rising.

For example, Savills research shows that the disruption from the coronavirus pandemic in the traditional retail and office sectors will drive a further decline in the average lease length attached to typical property investments. This means the traditionally largest and most liquid parts of the investment market – retail and office – will no longer offer the level of annuity matching that they used to. To offset this, Savills forecasts rising capital allocations into the residential sector, namely multifamily and senior housing.

It is the long-term appeal of residential, demand for which is driven by global demographic factors rather than the cyclical health of the economy and the recent effects of Covid-19, that is of greatest value to pension funds. Expect to see Czech pension fund managers taking more of an interest in real estate, particularly residential as well as logistics and data centres, over the coming decade.

.jpg)

.jpg)