Government attention appears to be turning yet again to the supposed problem of land banking. The Local Government Association recently called for powers to charge developers council tax on unbuilt homes, and the Housing Minister confirmed that he is planning to take action to ensure developers build out at pace. However, our analysis shows that, far from sitting large amounts of undeveloped land, developers are facing shortages of consented land, particularly in less affordable areas where there is the greatest demand for new homes and the highest potential to deliver at pace.

The impact of the pandemic on land supply

In the year to September 2020, full planning permission was granted for 370,800 new homes in England, an 8% fall from the 2019 peak of 406,000 consents. However the number of homes approved in Q3 2020 grew by 21% against the previous quarter, suggesting that disruption to the planning system due to lockdown has been relatively short term.

Certainly, looking at the national figures, the planning system does not appear to be a barrier to increasing housebuilding to meet the Government’s ambition of delivering 300,000 homes per year by the middle of the decade. Rolling annual planning permissions have exceeded 300,000 homes since Q1 2017, helping to build a strong pipeline of development land.

Homes in the Right Places

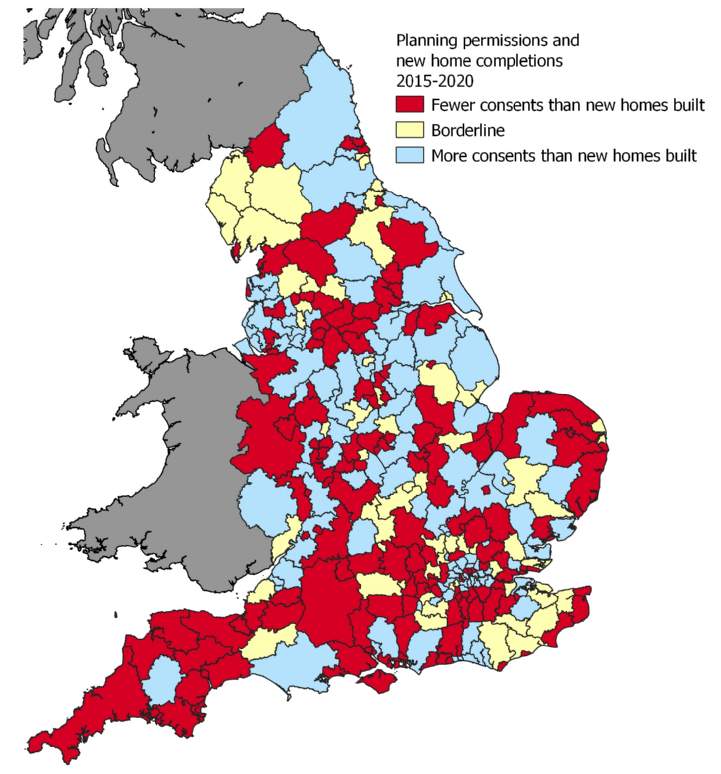

But this pipeline is not distributed across the country in line with the areas where new homes are most needed and demand is strongest. The standard method for calculating housing need was introduced in 2017 to help streamline the planning system by providing a single assessment covering all local authorities in England. In its simplest form, the standard method uses house price to earnings ratios to generate a multiplier which is then applied to household projections for a given area, effectively using affordability as a proxy for housing demand.

To some extent, the standard method is beginning to achieve what it set out to do. In the year to Q1 2018, the least affordable fifth of all local authorities ( the areas where there is the greatest need for more housing) contributed 24% of all full planning consents granted on sites of over 20 units. By Q3 2020, this figure had risen to 31%. However, over the same period, the second least affordable quintile of local authorities saw their contribution to planning consents fall to just 14% of the national total. The most affordable quintile, where there is a lower need for housing has consistently delivered 20-25% of all consents.

.jpg)