Will Covid-19 accelerate a trend towards regional supply chains and nearshoring?

The disruption associated with Covid-19 brought the resilience of manufacturing supply chains into sharp relief. China has long played a dominant role in global manufacturing, but rising labour costs, the US-China trade war and most recently Covid-19 has led to a reassessment of increasingly stretched global supply chains. Calls are growing by some to bring supply chains and manufacturing closer to final destination markets. What does this mean for global trade flows, and what are the real estate implications?

AN ACCELERATOR RATHER THAN A DISRUPTOR

The US-China trade war, which began in 2018, had already started to re-shape global manufacturing and supply chains. US manufacturing imports from China declined by 17% in 2019, a total fall of $90 billion. This served to boost trade with other parts of the world, with US trade from other Asian low-cost countries increased by $34 billion in the same year. Mexico was a major beneficiary, with exports to the US rising by $13 billion. The trend continued in the first three months of 2020, intensified by Covid-19, as US manufacturing imports from China were down by 29% in Q1 2020 compared to Q1 2019.

The Covid-19 pandemic turned supply chain resilience into a global, increasingly politicised, issue

Savills World Research

The Covid-19 pandemic turned supply chain resilience into a global, increasingly politicised, issue. French President Macron has called extensive offshore manufacturing or delocalisation ‘unsustainable’. Japan’s recent Covid-19 stimulus package includes subsidies for firms that repatriate factories, while India’s prime minister has spoken about a ‘new era of economic self-reliance’.

But supply chains are complex and tangled. It is never as simple as closing a factory in one location and opening one in another. Relocating manufacturing is costly so redirecting future investment is a more likely trend. The perceived benefits of nearshoring will also vary depending on the type of good. Some sectors, such as automotive, are already largely organised at a regional level.

COST: A KEY PART OF THE MANUFACTURING EQUATION

China’s comparatively low labour costs are one factor that helped the country become the major player in global manufacturing. Low land costs, favourable tax legislation, good infrastructure and skill base are also factors. The Belt and Road Initiative further established the country’s dominance, forging stronger political, economic, social, and trade ties with the neighbouring countries and in turn opening up new markets for China’s exports, and imports.

But as China developed its cost competitiveness has been eroded. Unit wage costs (the average cost of wages per unit of output) for manufacturing have risen by 285% over the past 20 years. By comparison, manufacturing unit wage costs in India, Thailand, and Cambodia have increased 132%, 26% and 12% respectively in the last 20 years. Only Vietnam has seen manufacturing unit wage costs increase by comparable levels, up 270% of the same period, although wages remain half those of China’s.

NEARSHORING POTENTIAL: A TRADE-OFF BETWEEN COST AND DISTANCE

For manufacturers, labour isn’t the only critical cost. Energy costs are a major component. Quality infrastructure, a favourable trade and regulatory environment and some existing manufacturing export base is also important. We have combined these factors to compare the manufacturing nearshoring potential of countries in proximity to the major consumer markets in an era of supply chain diversification (see chart).

Asia Pacific

Vietnam tops this index, befitting from low labour and electricity costs and a manufacturing base that was already growing quickly. Troy Griffiths, Deputy Managing Director of Savills Vietnam adds, “A policy of energy security has been pursued by the government, leading to huge new investment in solar power together with the Bac Lieu LNG project. Ever more globally integrated, the Vietnam National Assembly have recently ratified the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement that will grow European trade access. Vietnam’s attractiveness is being further boosted by government reform, a strong anti-corruption drive and most recently the country’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.”

Other low-cost regional hubs developing as alternatives to China in Asia Pacific include Indonesia (3rd) and Thailand (7th), where labour costs are under half those of China’s.

Taiwan, China, already a major tech manufacturing centre with a strong skill base, ranks 6th. Unaffected by tariffs associated with the US-China trade war, major computer and data centre server production has been diverted to the province. A favourable business and trade environment is complemented by excellent infrastructure.

Despite seeing a rise in labour costs in recent years, China remains a highly competitive market. Offering a deep labour pool (some 220 million people are employed in industry), the country has also moved progressively up the value chain in recent years with specialist manufacturing expertise in many sectors. These factors enable a level of scalability, speed and reliability that will continue to underpin China’s importance in the coming years.

Higher cost markets in the region such as Singapore perform well (12th) thanks to exceptional logistics and export links and openness to trade. Automation (see below) will be key to unlock the nearshoring potential of markets such as Singapore, however, where suitable buildings and production workers are in short supply.

India, one of the few countries with a labour force that comes anywhere close to rival that of China, ranks 16th. Low input costs (labour and electricity) are offset by a lower than average infrastructure and trade openness score. Nonetheless, in 2019, India was one of the top 10 recipients of foreign direct investment (FDI) globally, totalling $49 billion, an increase of 16% from the previous year. The Indian government recently allowed up to 100% FDI in contract manufacturing, aiming to increase the share of investments in manufacturing more broadly.

Europe

The countries that offer greatest nearshoring potential in Europe are concentrated in Eastern Europe, thanks to lower input costs and direct road and rail links to the major Western European consumer markets. Ukraine is first for Europe (2nd overall), thanks to very low wage costs by European standards. Already a major agricultural exporter, there is nearshoring potential in manufacturing supported by an open trade environment. Serbia (4th), another low-cost market, benefits from a strategic location that offers the easiest overland travel between Europe and Asia Minor and beyond.

The countries offering greatest nearshoring potential in Europe are concentrated in Eastern Europe, thanks to lower input costs and direct road and rail links to major Western European consumer markets

Savills World Research

The Czech Republic follows (5th), supported by excellent infrastructure, favourable input costs and an established manufacturing economy for export. A major automobile manufacturer, electronics manufacturer Foxconn also has a base in the country. In 2019 the Czech Republic exported goods equivalent to 74% of the country’s GDP and there is scope to further develop as a regional nearshoring destination, particularly given the presence of existing major global manufacturers.

Russia (9th) is positioned to serve both European and Asian markets. Russian labour costs are now comparable to China’s in dollar terms, thanks in part to a rouble that has fallen by around 50% against the dollar in the last 10 years.

Following Hungary (11th), Morocco (ranked 13th) is already emerging as a key textiles manufacturing centre with easy access to Western Europe.

North America

In the Americas, Mexico is the highest-ranking country among those we surveyed, positioned 15th overall. Low labour costs (a tenth those of the US) have established it as an important manufacturing market in proximity to the large US consumer market, securing it as a key nearshoring destination.

The US and Canada, like higher cost Northern and Western European countries, score lower overall for nearshoring potential. High labour costs are a barrier to onshoring at scale in the major Western consumer markets, however, there is scope for more critical or less price-sensitive goods to be produced locally.

COULD AUTOMATION BE A SOLUTION IN HIGHER COST MARKETS?

Automation in manufacturing can help to offset labour costs, particularly important in higher-cost markets. It can also provide a hedge against future labour market disruption. The challenge in today’s economic environment, however, is the large upfront capital expenditure it requires. In some markets, there are political sensitivities since low-income jobs are often the most vulnerable to automation. Longer term, automation is likely to play more of a role, however, particularly as the technology becomes cheaper.

THE FUTURE OF GLOBAL LOGISTICS

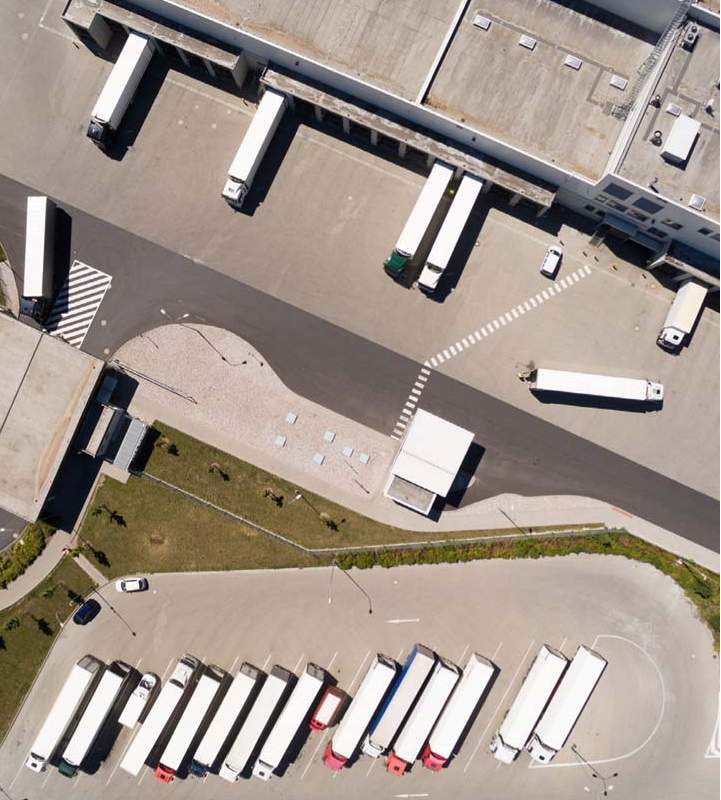

Changing manufacturing bases have the potential to shift trade flows and in turn the dynamics of global industrial and logistics markets.

Morocco, for example, is easily accessible to Western Europe by ferry and could further integrate into the existing logistics corridor that spans the ports of southern Spain, the Iberian peninsula into France. Growth in exports from here could boost demand for logistics at strategic entry points, such as Algeciras, Valencia and Barcelona.

The effect is already been seen in parts of Asia. Land prices and rents in Vietnam are rising sharply as the nation becomes a major manufacturer. Industrial rents in Binh Duong, a district to the north of Ho Chi Minh City, rose 54.4% in the year to June 2019. Industrial landlords in India have reported an uptick in light industrial occupation in their parks, particularly in ancillary automobile industries.

Logistics real estate typically accounts for just 0.75% of total distribution and warehousing costs. Availability rather than cost, therefore, is increasingly the challenge, with exceptionally low vacancy rates characterising many markets, compounded by the delivery of new space delayed by lockdowns.

Across Europe, the average logistics vacancy rate is just 5% (see chart). In Asia, supply is even tighter in some major markets, with vacancy rates in Beijing and Tokyo under 2%.

Putting further pressure on these very low vacancy rates, in the wake of Covid-19 some distributors sought multiple sites in one location to protect themselves against future disruption. Together with increased levels of stockpiling, this served to boost demand in the short term.

Longer term, nearshoring may serve to weaken demand for warehouse space in the manufacturer’s host country.

Kevin Mofid, Director of Savills Industrial and Logistics research says, “With more regionalised supply chains, manufacturing businesses would need to hold less stock at any one time due to shorter delivery times, meaning potentially smaller space requirements closer to home. Instead, the increased inventory holdings will be pushed further down the supply chain and may, therefore, benefit the countries higher up in our index. Automation to improve efficiency in terms of space and resources needed in the distribution process could also mean less overall square footage is required, but values may increase as the best-located sites can be used more intensively.”

A protracted global economic downturn may also serve to slow the growth of occupier demand, although the broader shift to online should offset any decline in demand from bricks and mortar retailers.

WHERE ARE WE HEADED?

We expect to see greater diversification of supply chains in the near term, with rising levels of nearshoring. Full-scale onshoring is likely to be limited to critical or less cost-sensitive goods, though longer-term increased automation in the manufacturing process may play a role. The rising ESG agenda will increasingly mean that low labour costs alone will not determine supply chain procurement decisions. All this will lead to more regionalisation, rather than full-scale localisation, of supply chains.

China’s role as a major manufacturing centre will remain, but in a move away from the dominance of a single manufacturing market, smaller hubs and spokes in the supply chain may emerge and this could benefit multiple markets.

Those countries that strike the balance between proximity to major consumer markets, lower input costs and favourable business environments are likely to benefit first.

We expect to see a range of countries in proximity to the major consumer markets grow in importance in the regionalisation of supply chains. These will include lower-cost locations such as Vietnam, Thailand, Eastern Europe, Morocco and Mexico, as well as higher cost markets such as Taiwan which offer significant trade advantages and skills bases.

In the near term, there is the challenge of a significant fall in consumer demand and trade given the economic implications of Covid-19. Consumer appetite for higher costs associated with any large-scale shifts in global supply chains is likely to be limited. Getting the right balance between cost and resilience against future disruption will therefore be key.