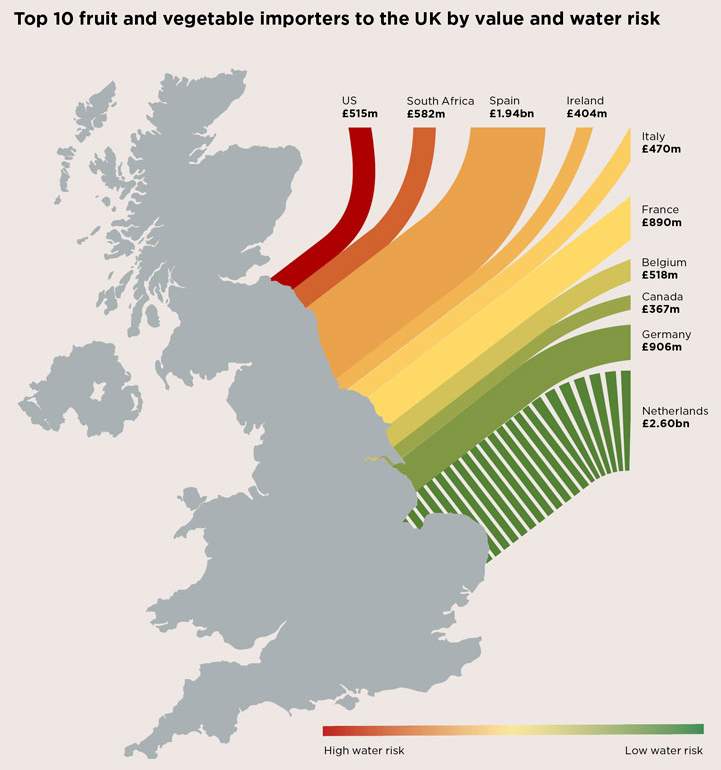

Over half of the UK’s fruit and vegetables come from more water insecure nations than the UK itself

In 2018, the UK imported £14 billion worth of fruit and vegetables. The map above shows the top 10 nations of origin for those imports, which accounted for almost two-thirds of imports in 2018 (by value). Over half of that value comes from areas where water is scarcer than in the UK. Spain, where climate change and poor water infrastructure is hampering agriculture’s efforts to produce food, exports nearly £2 billion worth of produce to the UK. However, CEA increasingly offers opportunities for the same produce to be grown in the UK.

Spain exports nearly £2 billion worth of produce to the UK. However, CEA increasingly offers opportunities for the same produce to be grown in the UK

Savills Rural Research

Our data highlights another traceability concern with international imports. Figures for the Netherlands as a producing country are good, but the “Rotterdam effect” misleads the true sustainability of imports coming from there. The port of Rotterdam serviced around 13.7 million containers in 2017, making it one of the busiest ports in the world. Despite the Netherlands appearing as both the largest and most secure importer, it is likely that an amount of that produce does not originate in the Netherlands. Instead, produce reaches the EU via Rotterdam and is then distributed from there. The security of these imports is therefore even more uncertain.

Source: Savills Research, HMRC, EIU

How trade flows can be disrupted

Qatar imports around 90% of its food, something it became very aware of when its neighbours accounting for 33% of its food imports cut diplomatic ties. The blockade by Egypt, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the UAE cut off land and sea trading routes. While something of an extreme example, Qatar’s $1.2 billion agricultural trade deficit is significantly less than the near $6.3 billion deficit shown by the UK. Recent political events also show that those trade flows are not entirely invulnerable to disruption.

Investing in security

Singapore only dedicates 1% of its 724 square kilometres to agriculture, meaning it only produces 10% of its total food requirements. The small island nation hopes to increase that to 30% by 2030 by investing over £120 million in research and technology. Thirty vertical farms already contribute to the near 12,000 tonnes of leafy vegetables grown each year. That will have to increase to over 30,000 tonnes to hit the target; an undertaking that will inevitably require further investments in agritech.

Read the articles within Spotlight: Controlled Environment Agriculture below.

.jpg)