.jpg)

Retail is reinventing itself once again, as it has throughout history. The fact that there is deep-rooted change afoot, even disruption, is undeniable. This newfound awareness is shaping today’s investment market. It is channelling demand towards safer, higher-quality assets, encouraging the search for new concepts, and calling for new real estate investment criteria. All these changes are only just beginning, they will take time, but they give us a glimpse of the exciting future ahead.

Lingering doubts cast long shadows...

… or when good news is no longer (quite) enough to remove uncertainty.

History has shown that there are times when our long-held certainties and beliefs seem to vanish into thin air and we reach a tipping point. Optimists call it evolution, pessimists call it crisis, and philosophers talk about new phases. Inevitably, these periods go hand-inhand with instability and uncertainty. This is right where retail currently finds itself.

From better awareness to exaggerated fears

Affected by the rise of online shopping and sometimes contradictory consumer expectations, major retailers throughout the developed world are immersed in a process of a long and difficult transformation.

In France, Carrefour has embarked on a restructuring plan, despite seeing improved Q3 2018 sales, while Casino has announced the closure of 20 hypermarkets and is ramping up asset sales in an effort to reassure its investors. Meanwhile, Leclerc’s growth has stalled, and Auchan is faced with reduced profitability and activity levels in its hypermarkets. Beyond France things are no different, Tesco is still struggling in the UK, while south of the Pyrenees, DÍa, a former Spanish giant, has been relegated to the “penny stock” category, with its share price now dipping below the €1 mark.

The difficulties facing major retailers are also being felt by the malls and shopping centres that house them; supermarkets and hypermarkets no longer have the same pulling power they possessed a few years ago.

City centre retail is not immune to these issues either. The mainstream fashion sector, which plays a crucial role on the high street, is struggling, the market has lost 14% of its value in the last 10 years for example1 . Many fashion retailers, particularly entry- and mid-level brands, are rationalising their store networks. Even success stories such as H&M and Zara are feeling the heat and closing some stores.

Some now say there are too many retail spaces, and that following the expansion seen in the 2000s, perhaps the time has come to reduce global retail space. The town centre department store model is also being challenged. In the UK for example, House of Fraser is closing stores, and BHS has shut up shop for good. Almost everywhere in Europe, retail activity is concentrated on arterial routes at the expense of city centre streets and entire districts. Traditionally confined to rural towns, vacant premises are increasingly a feature of mid-sized town centres, to the extent that there are occasional whispers of “ghost towns”– in March 2017 Albi was the subject of a controversial article in the New York Times.

Key players and entire sectors in retail are seeing the sustainability of their business models called into question. These doubts are inevitably having an impact on the retail investment market. Some real estate companies have decided against certain sales due to a lack of interest from buyers, or valuations below their expectations. This was the case for shopping centres such as O’Parinor in Aulnay-sous-Bois, and Espace Saint-Quentin in Montigny-le-Bretonneux.

Strongly drawn to retail assets just one or two years ago, investors now seem to have been enticed away by other temptations. To paraphrase Khalil Gibran, “love and doubt have never been on speaking terms”, it would appear that the lack of interest in retail is as sudden as it is complete.

From perception to reality

Yet, as is often the case, the reality is far more complex and compelling than the one painted by this simple picture. The fact that there is deep-rooted change afoot, even disruption, is undeniable. Retail is reinventing itself once again, as it has throughout history, ever since the dawn of modern trade, when shipping linked Europe to Asia and America in the 15th century.

For many today, it is still a question of transport, delivery, stock management and globalisation. This new revolution is changing the rules of the game and questions principles that seemed set in stone. Logically, investors are being more careful, weighing up their options, calculating risks, and refusing the bidding frenzies we have become familiar with.

It is by no means the end of bricks and mortar retail. Although consumer habits have changed, people are still spending, and the expertise and enthusiasm necessary to maximise the performance of retail spaces do exist.

This newfound awareness is shaping today’s investment market. It is channelling demand towards safer, higher-quality assets, encouraging the search for new concepts, and calling for new real estate investment criteria.

Today’s newfound awareness is channelling demand towards safer, higher-quality assets, and calling for new real estate investment criteria.

Cyril Robert

It’s not all plain sailing

To talk of a lack of interest when a market grows 17% y-o-y would be absurd.

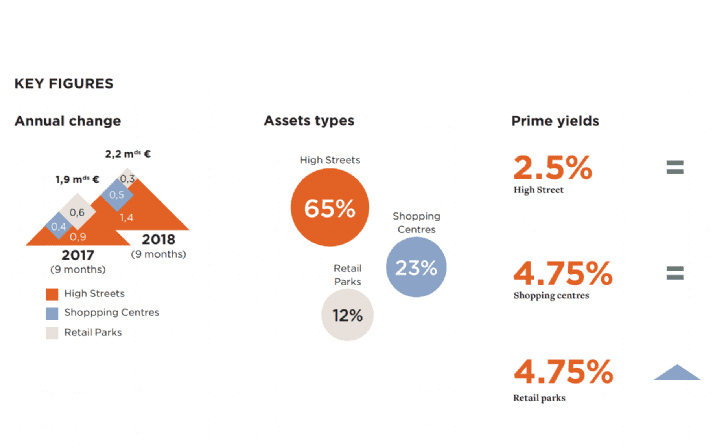

Yet retail investment volumes grew by precisely this amount. Over the first nine months of 2018, more than €2,200 million was invested in France, compared to €1,900 million over the same period in 2017.

This upward trend is set to be confirmed in the coming months, with large deals due to be completed. Casino, for example, which is in the midst of a major debt reduction plan, has confirmed two portfolio sales. The first involving 55 Monoprix stores (19 of which are located in the Ile-de-France region), acquired by Generali Real Estate for €565 million. The second should see AG2R La Mondiale (AGLM Immo) buy another 14 Monoprix stores for €180 million. In total, Casino will therefore have sold €745 million of town centre real estate assets across two transactions.

As for out-of-town retail assets, the sale of the former Myrina portfolio, divided into sub-portfolios, is expected to reach a total volume of circa €500 million. Compagnie Frey is in the process of divesting assets valued at almost €200 million – Epargne Pierre, Groupe Voisin’s (Atland) real estate investment trust (SCPI), has just acquired the Cormontreuil assets for more than €90 million.

All signs point towards 2018 registering decent year-end results in terms of investment volumes. Despite apparent concerns, the year could be compared to a leisurely cruise that carefully guides passengers to their next destination, where the right wardrobe is all that is needed to arrive well prepared.

Nevertheless, figures can sometimes be deceiving, as the sea of retail is never as calm as it might appear. Indeed, the growth seen since the beginning of the year is based on the mediocre results achieved in 2017, and the high of 2014 is still a long way off (€3,700 million invested in nine months). In addition, activity in 2018 is restricted to a very limited number of transactions, down by almost 47% y-o-y.

As such, we must not let the growth in investment volumes mask the limitations of the retail sector – which represents just 12% of commercial real estate investment in France – nor its increasing concentration on specific assets.

High street – the star of the show

The market’s apparent health is mainly thanks to the draw of city-centre retail (particularly the case for the Monoprix stores): growth in investment volumes in this asset class is spectacular (up +55% y-o-y), with high street retail units, mainly in Paris, accounting for 65% of investment activity since the beginning of the year. The high street retail unit is the star asset class, best-positioned to weather the profound changes in spending habits as it can still count on the “impulse buy” and is boosted by tourist activity – which is thriving in 2018. Caution is needed nonetheless; the sale of the flagship Apple store on the Champs Elysees for almost €600 million (a property also featuring office space), significantly skews the figures. Although this mega-deal will always temporarily inflate the results given its sheer size, it reflects the confidence that this type of prime location asset inspires. High street yields remain at their lowest level, once again reflecting strong investor appetite, with several deals – including the Apple deal – signed below 2.5%. Investment market results are much more mixed for other retail segments, however, it is fair to say that the figures do not give us the whole picture.

.jpg)

Investment market figures are not yet reflecting the growing interest in retail parks.

Retail parks – the new safe-haven

Retail parks and the out-of-town retail segment are the perfect example of this. Since the beginning of 2018, it appears to be down y-o-y, with the first nine months of 2018 recording just over €260 million (-54%). However, this underperformance is only superficial and is mainly due to lengthy completion times for asset sales. The large number of deals currently being negotiated should allow investment volumes to pick up over the next few weeks and months.

The 11th hour signing in September of Real IS’ acquisition of the Eden 1 park in Servon for almost €50 million (yielding 4.75%) acted as the starting gun for several other deals. Q4 2018 will, for example, see the sale of Allées de Cormeilles, 22,000 sqm in Cormeillesen-Parisis. A rate slightly inferior to 5.00% is announced. Enthusiasm for these assets is driven by their efficiency, both economic and operational: simplified management, controlled real estate costs (stable rents and low charges) and attractive yields – all clearcut advantages today.

The fact that yields remain stable for this type of asset (4.75% prime yield), says a lot.

Shopping centres under pressure

In contrast, investment volumes in shopping centres have grown by 25%, reaching just under €500 million. Yet this is the segment that appears to be suffering the most today. The growth observed cannot hide the relatively low level of activity (23% share of the market), restricted to just seven deals since the beginning of 2018. For example, the Grand Vitrolles sale alone represents more than 30%. Neither can the registered growth hide the yields at which these sales were closed, with the prime yield regaining 50 basis points in one year to reach 4.75% at the end of Q3 2018. For secondary retail arcades, the increase is even clearer (a minimum of 125 basis points), with the average yield coming in at 6.75%, and sometimes even reaching 8%. Such a deterioration reflects investors’ overall scepticism for large assets which are complicated and expensive to manage.

An active, but selective, market

Although negotiations are taking longer, due diligence is increasing, and the number of potential buyers is dwindling, it does not mean that there is a widespread loss of interest in investing in retail. Rather, for a deal to go through, investors must be convinced of the strength of the asset’s commercial positioning and the fundamentals of its catchment area, while sellers must be realistic when it comes to the asking price.

The lines have been drawn, the retail investment market in 2018 will neither wow nor will it be uniform; it will be limited to a reduced number of transactions (likely to increase its volatility in the future), but it is certainly not on the ropes. Like retail in general, it is simply going through a period of transformation. The solutions emerging around adapting retail formats, organisation and business models will gradually give certain players piece of mind and enable them to drop their ‘wait-and-see’ approaches.

Nonetheless, it will take time for these solutions to become more clearly defined.

Towards co-retailing and mixed-use

What solutions exist for fragile assets?

Current concerns are mainly related to the future of secondary assets – high street retail units located away from the main arterial routes, in mid-sized towns, as well as shopping centres with limited catchment areas. There are real worries about the lack of interest in such spaces and their potential decline – fears that they could suffer the same fate as several industrial monoliths in the 60s and 70s.

There will be no one-size-fits-all model to define or redefine the function, vocation, use (and therefore value) of these assets: several different solutions are emerging, solutions which can be combined and will require real expertise, as well as capital.

In the absence of the necessary resources (capital, time and know-how), landlords will most likely be forced to choose between the inevitable deterioration of their assets, or their sale to specialist investors, who will be demanding in terms of valuation. As such, reductions in price are to be expected.

Engaging customers on an emotional as well as a commercial level

What solutions are emerging? Most revolve around one central theme – developing personalised relationships with the customer and showing sensitivity towards the local environment. This is the recipe for a more successful future. The retail space and its occupier are not only there to make standardised merchandise available to customers, but to offer exclusivity and personal service, to provide spaces for people to socialise, and to become ambassadors for producers. Retail needs to get back in touch with its local customers and roots.

It isn’t pie in the sky, some retailers are already trying it and succeeding – as is the case for Grand Frais, French consumers’ favourite brand in the 2018 OC&C rankings.

Launched in 1992, the food specialist now has over 210 stores in France. On average, it opens around 20 every year, has a turnover of €1,500 million and apparently enjoys margins more than double those of its retail competitors. Its business model? In just under 1,000 sqm of retail space, taking inspiration from indoor food markets and managed by self-employed artisans, a Grand Frais store has meat, cheese and fish counters, fruit and vegetable stalls, some dry groceries and in certain cases, a bakery. The produce is all high quality, primarily locally sourced and in limited amounts, which keeps stock costs down and flows easy to control. While the checkout process and general services are centralised, each counter or stall is managed by a qualified expert who pays rent and royalties to Grand Frais. The result? More staff (around 20% more) than in similar-sized supermarkets, who are available to cheer, advise and sell to the customer. It is a type of co-retailing, similar to the co-working model emerging in the office sector.

The big mix

The “shop in shop” concept is linked to this transformation – it involves dedicating some space to another brand or manufacturer within a store. Darty has developed its own corners within different Fnac stores and is about to take over the domestic appliance franchise in Carrefour hypermarkets. Both partners hope it will be a “win-win”. Carrefour will be able to: diversify its offer and services by working with a well-known specialist brand; increase footfall in its stores; and share costs linked to its retail spaces. Darty, on the other hand, will gain visibility and become better known, by reaching more areas of the country at a low cost; by benefitting from the hypermarket’s footfall; and by tapping into a new client base.

A different example is Jardiland and Gaarden, who have joined forces to offer a personal gardener in 32 garden centres. Another variation on the same theme: improving services, increasing proximity to the customer, joining brands and sharing knowhow and skills.

The trend is not limited to France: in the UK, Natoora (a fruit and vegetable specialist) has opened spaces in Selfridges and Waitrose, while Ford has unveiled a car showroom in Next’s store at Manchester’s Arndale shopping centre.

This model, which Grand Frais best illustrates currently, cannot be replicated by everyone everywhere, but its success speaks for itself, and can serve as inspiration. It is worth noting here that while Grand Frais jumped from 7th to 1st place in the OC&C rankings in one year, the internet “pure-players” disappeared from the top 10. Amazon was number one from 2013 to 2016, but dropped to 5th place last year, with the Seattle giant continuing its freefall this year, tumbling to 12th place.

The future of some retail spaces will also require a complete or partial conversion, with a mix of different uses, including accommodation and residential space with services (particularly in city centres), lastmile logistics, after sales service, or even high value-added agriculture. It wouldn’t be the strangest thing ever: after having been (rightly) accused of contributing to urban sprawl and the loss of green space, retail could now contribute to reversing or repairing the damage.

All these changes are only just beginning, they will take time, but they give us a glimpse of the exciting future ahead. A future requiring sound analysis and expertise that will undoubtedly cause the market to narrow, with fewer but more highly qualified operators.

Specialists who will actively address both doubts and concerns, and who will certainly step up and act. Because, as Leonardo da Vinci once wrote: “he who has no doubts will achieve very little”.